Dicrocoelium dendriticum is a type of trematode that can inhabit the human liver and potentially cause disease and infection. This post will provide a detailed examination of this parasite and its characteristics.

Dicrocoelium dendriticum, commonly known as the lancet liver fluke, is a fascinating parasite with a complex life cycle involving multiple hosts. Discovered by Rudolphi in 1819, this flatworm has intrigued scientists for centuries.

What is D. dendriticum? [Morphology & Characteristics]

Dicrocoelium dendriticum resides in the small bile ducts and gallbladder and is globally distributed. It is found in almost all parts of the world, including Europe, Asia, Africa, and America.

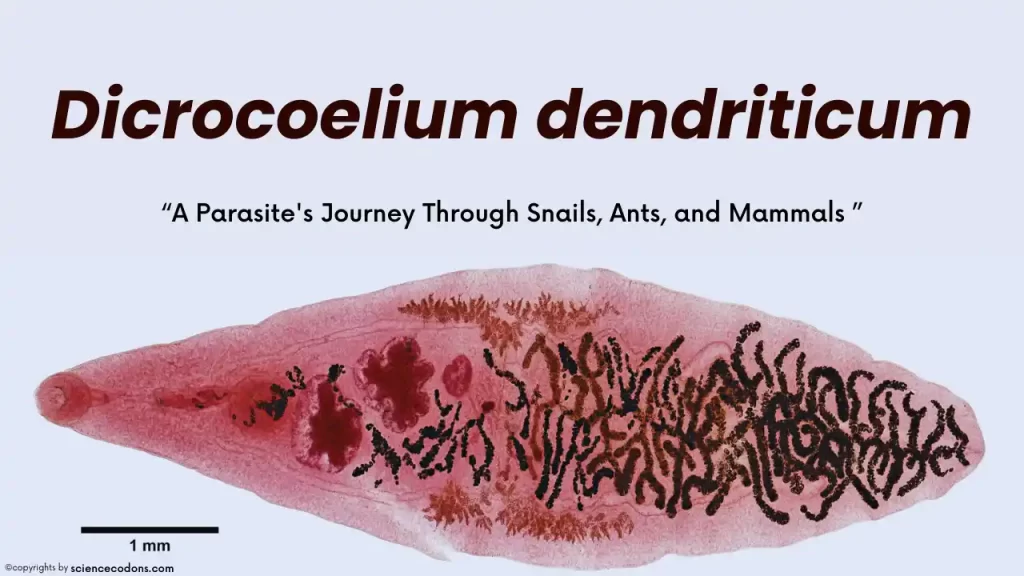

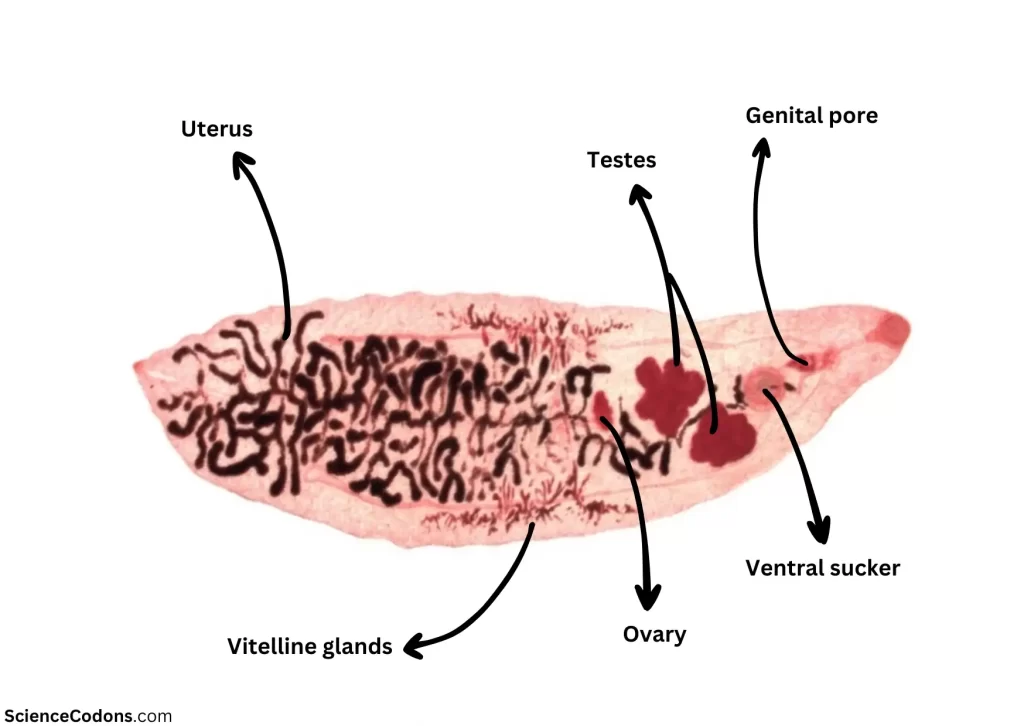

- The worm typically measures between 0.5 to 1 centimeter in length and 1.5 to 2.5 millimeters in width.

- It has a lance-like shape.

- Unlike other trematodes such as Fasciola hepatica and Fasciolopsis buski, the reproductive system of D. dendriticum is arranged in a TTO pattern, meaning the testes are located above the ovary.

- Dicrocoelium dendriticum thrives in dry conditions.

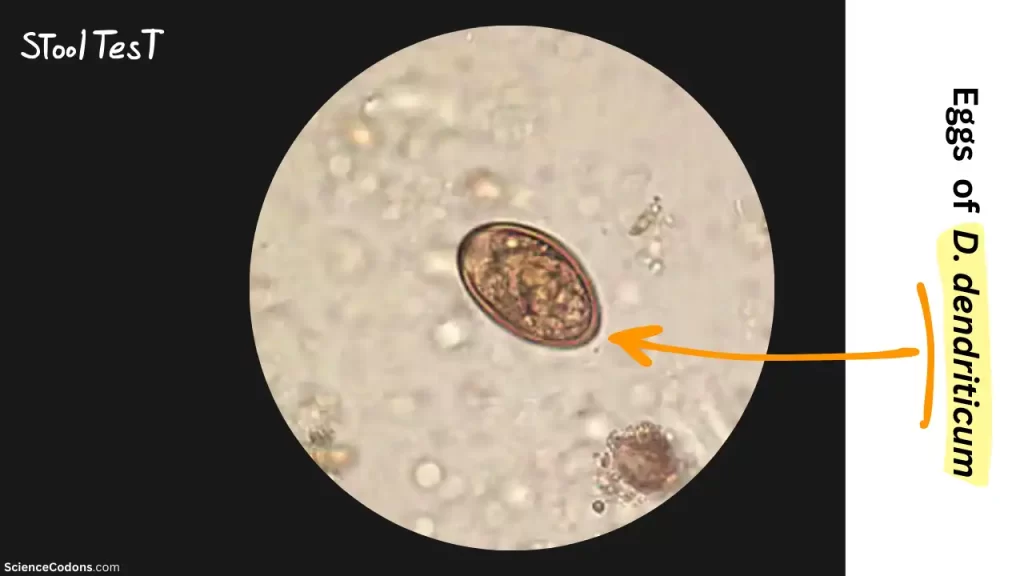

The eggs of this worm are usually 30 by 45 microns in size. They are double-walled, thick, and mature, yellow to brown.

Hosts Infected by D. dendriticum

- The final hosts can be cattle, sheep, and goats. Humans can also serve as accidental hosts.

- The first intermediate host is terrestrial snails, such as Cionella lubrica.

- The second intermediate host is ants, specifically Formica fusca ants.

Life Cycle of Dicrocoelium dendriticum

The final host, in whose bile ducts and gallbladder the worm resides, excretes mature eggs with feces. The first intermediate host, terrestrial snails, ingests these eggs. Inside the snail’s body, the sporocyst stage occurs twice, resulting in the formation of cercariae.

Interestingly, the rediae stage does not occur in D. dendriticum. Instead, the sporocyst stage repeats twice, eventually leading to the expulsion of cercariae from the snail’s body within gelatinous masses. These masses are left behind as the snail moves and are consumed by the second intermediate host, ants. When ants ingest these gelatinous masses, they also consume the cercariae. Inside the ant’s body, the cercariae induce the formation of the metacercariae stage. Some metacercariae form in the ant’s head, causing the ant’s jaws to lock!

While moving on plants and consuming leaves, the ant experiences muscle spasms and jaw-locking induced by the metacercariae. The ant becomes immobilized and is eaten by the main hosts, which are herbivores, or accidentally by humans. Inside the final host’s body, the ant is digested, and the metacercariae migrate to the liver’s bile ducts, where they mature.

The life cycle of Dicrocoelium dendriticum, from when the main host eats the ant infected with metacercariae until adult worms form in the bile ducts, takes about 6-7 weeks. After this period, the worms begin to mate, either hermaphroditically or through cross-mating, and start producing and excreting eggs.

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Embryonated Eggs | Eggs containing miracidia are shed in the feces of definitive hosts (typically ruminants). |

| First Intermediate Host (Snail) | Miracidia hatch from the eggs, migrate through the snail’s gut wall, and settle into adjacent vascular connective tissue, becoming mother sporocysts. |

| Daughter Sporocysts | Mother sporocysts migrate to the snail’s digestive gland, giving rise to several daughter sporocysts. |

| Cercariae Production | Inside each daughter sporocyst, cercariae are produced. |

| Respiration Chamber (Slime Ball) | Cercariae are shed in a slime ball from the snail. |

| Second Intermediate Host (Ant) | After an ant ingests the slime ball, cercariae become free in the ant’s intestine and migrate to the hemocoel, where they become metacercariae. |

| Definitive Host (Human or Other) | When a suitable definitive host eats an infected ant, the metacercariae excyst in the small intestine. The worms then migrate to the bile duct, becoming adults. Humans can be definitive hosts after ingesting infected ants (e.g., on contaminated food items). |

Symptoms & Pathology of Dicrocoeliasis

Mild infections of Dicrocoelium dendriticum typically present no symptoms. However, severe infections can lead to liver cirrhosis, anemia, edema, weight loss, and emaciation. Notably, these infections usually do not generate significant immunity. This means that if an individual gets infected, they can be re-infected later.

| Symptoms | Description |

|---|---|

| Cholecystitis | Inflammation of the gallbladder. |

| Liver abscesses | Pockets of pus within the liver tissue. |

| Generalized gastrointestinal/abdominal distress | Vague discomfort or pain in the abdominal area. |

| Occasional cases involving flukes in subcutaneous masses | Rare instances where the flukes are found in subcutaneous tissues. |

Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosis of Dicrocoelium dendriticum is usually made through a stool test, where tiny eggs can be observed in the feces. Flotation can be used to detect these very small eggs, although they may not float well. This worm is most often identified in slaughterhouses, during the slaughtering process, in the liver’s bile ducts.

Anti-worm medications such as triclabendazole, thiabendazole, and albendazole are used for treatment.

Prevention and Control

To prevent and control Dicrocoelium dendriticum, it is generally recommended that infected animals be treated. These animals should undergo treatment 2 to 3 times a year. Control of intermediate hosts is also possible; terrestrial snails can be eliminated using molluscicides, such as cyanide. However, these methods are costly and have ecological side effects and environmental impacts.

In general, the first step in preventing infectious and especially parasitic diseases is personal care and hygiene. This is crucial as most routes of infection are through food or contact with contaminated hands with the body’s entry points.

Conclusion

The lancet liver fluke is a testament to the intricate relationships between different species in our ecosystem. Its life cycle highlights the interconnectedness of nature and underscores the importance of understanding parasitic diseases that can affect both animals and humans.

Reference

- MANGA-GONZÁLEZ MY, GONZÁLEZ-LANZA C, CABANAS E, CAMPO R. Contributions to and review of dicrocoeliosis, with special reference to the intermediate hosts of Dicrocoelium dendriticum. Parasitology. 2001;123(7):91-114. doi:10.1017/S0031182001008204

- Tarry DW. Dicrocoelium dendriticum: The Life Cycle in Britain. Journal of Helminthology. 1969;43(3–4):403–16. doi:10.1017/S0022149X00004971

- Cabeza-Barrera, I et al. “Dicrocoelium dendriticum: an emerging spurious infection in a geographic area with a high level of immigration.” Annals of tropical medicine and parasitology vol. 105,5 (2011): 403-6. doi:10.1179/1364859411Y.0000000029-ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- https://jmums.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-6748-en.html

- Sauca Subías G, Planas Vilá N, Pérez Sáenz JL, Fernández Roure JL. False parasitism by Dicrocoelium dendriticum: presentation of 4 cases. Med Clin (Barc) 1989;93:359.

- Markell & Voge’s Medical Parasitology (10th Edition)